The World Health Organisation (WHO) has worked in various ways over the past decade for the mental health promotion perspective to have a greater impact, particularly among young people. It was given top priority back in 2010 [1] and since then the EU and WHO have had common agendas to highlight this topic [2]. Their message has been that the broad promotion of mental health is essential and should be viewed as an investment in the future. However, tangible, evaluated tools and methods for the arenas – particularly schools – to work with are still conspicuous by their absence [3]. Existing methods have been designed to prevent mental sickness and mental problems and not principally to promote mental well-being (further information in Research tab).

Initiatives are also underway in Sweden. In recent years, Forte has announced large grants for research into the mental health of young people. A welcome initiative also came from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) during the spring of 2019 to pool efforts relating to mental health [4]. One of the working areas within this joint effort involves equipping individuals to achieve their full potential and well-being. We consider that the SIM project fits in well with this work.

Theoretical framework and definition

When formulating new promotional initiatives, it is important to define theoretically what ‘mental health’ means, as this will affect both the formulation of the initiative itself and how it is followed up and evaluated. The theoretical basis of the Solution‑focused Intervention for Mental health (SIM) is WHO’s definition of mental health, which is one of the most quoted definitions in literature. It describes mental health as a general state of mental well-being in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community [5].

WHO’s definition shows that mental health is different to an absence of mental disorders or mental illness. It is something positive, a resource with its own value. This is also the reason why it should be recognised – measured, analysed and promoted – separately, including initiatives specially designed for that purpose [6,7]. This is very important from a public health perspective. It has been assumed (silently) for some time that as long as the prevalence of mental illness and mental problems is low in the population, then levels of mental health will be high. However, growing research has shown that high levels of well-being – that do not just reflect the absence of mental illness – independently predict not only a lower incidence of illness, but also have a number of positive effects on both individuals and society [8,9,10,11].

Mental health in the positive sense shown here includes both well-being and function – which can also been viewed as an expression of the two dominant traditions within scientific literature relating to mental health [6]. Well-being relates to one of them, hedonism, which deals with, among other things, positive feelings, being involved and satisfied with life [12,13]. Good function relates to the other, eudaimonism, which may involve self-acceptance, personal development, autonomy, the perception of meaning, social integration and social acceptance [7,14,15). The eudaimonic tradition thus includes both psychological and social aspects of function – elements recognised in WHO’s definition.

Operationalisation – measuring mental health

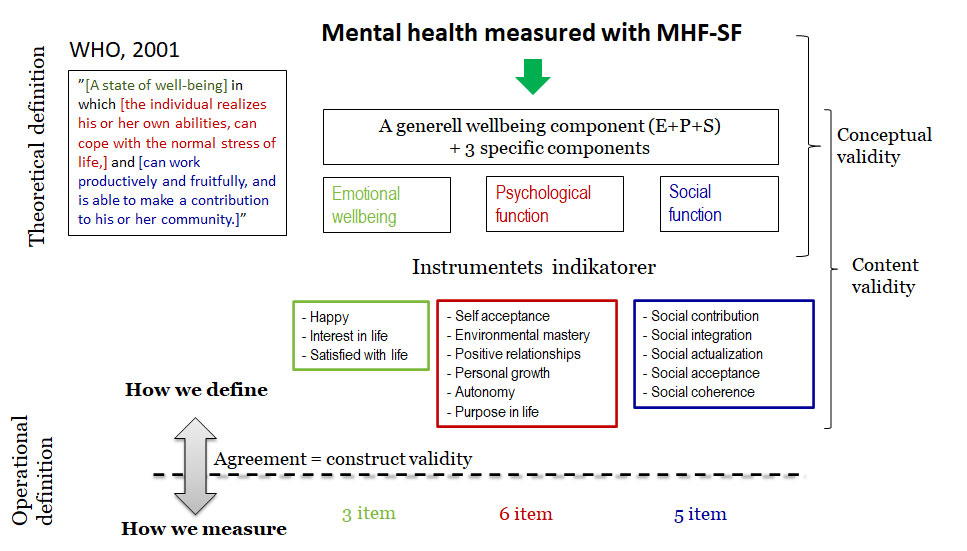

Keyes´ Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF) is one of the few psychometric evaluative and epidemiologically viable (i.e. not too extensive) instruments available for measuring mental health in a reliable way according to the descriptions above [16]. MHC-SF was originally produced in an American context but has since been evaluated and used in hundreds of studies throughout the world. A study conducted this year shows that MHC-SF also has psychometrically satisfactory properties when used with Swedish young people [17]. One advantage of the instrument in terms of its content is that it reflects relatively well the various elements of WHO’s definition. The figure below provides a schematic link between the theoretical and operational definition of mental health based on MHC-SF. Through ‘factor analysis’, it is shown that mental health measured using MHC-SF can be understood on the basis of first a general component of well-being – comprising both emotional well-being and social and psychological aspects of function – and second the three specific components of emotional, psychological and social well‑being. The analyses also show that the general component is the dominant one by explaining 73 per cent of the variation in the young persons’ mental health, while the specific components jointly explain the remaining 27 per cent. For a more technical and complete description of the link between the instrument’s indicators and latent factors [17].

A person responding to MHC-SF can state how often in the past month they have perceived three indicators of hedonic well-being and eleven indicators of eudaimonic well‑being – Never, Once or twice, Once a week, Two to three times a week, Almost on a daily basis or On a daily basis. The more frequently they have perceived them, the better their mental health. A person who has perceived at least one indicator of hedonic well-being and at least six indicators of eudaimonic well-being almost on a daily basis or on a daily basis over the past month may, based on MHC-SF, be classified as flourishing – i.e. have flourishing mental health. In other words, in order to be classified as ‘flourishing’, it is not enough to have felt happiness often, or just indicators of emotional well-being during the past month; you also need to have perceived a number of indicators of good function.

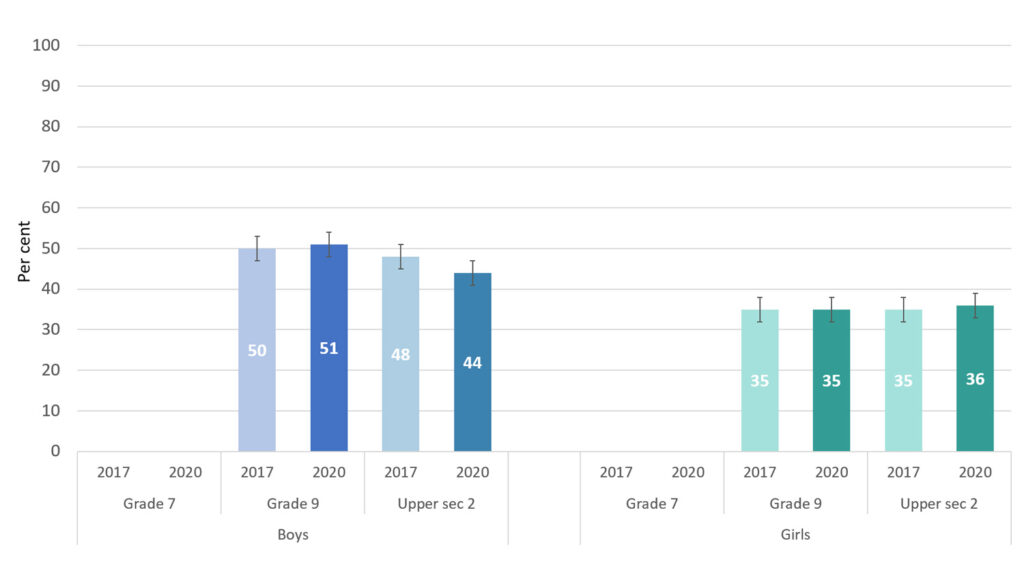

MHC-SF has been used in the Liv och hälsa ung [Youth Life and health] population survey from Västmanland since 2014 to track this kind of mental health. Analyses from the surveys in 2014 and 2017 show a statistically significant reduction in the mental health of students in School Year 9 at compulsory school and School Year 2 at upper secondary level. This reduction was primarily seen among girls and also people with one or more disabilities [18].

Furthermore, the 2020 survey shows that the proportion with flourishing – or, as sometimes referred to in Swedish, adequate mental health – among girls amounts to 36 per cent and, among boys, 44 per cent [19]. There is no significant reduction from the previous survey in 2017 – although a slight reduction can be seen for boys at upper secondary school – but the findings still show a clear need to work in a more promotional way so that more young people can achieve adequate mental health. And this is the aim of Solution-focused Intervention for Mental health (SIM).

The link between mental health and the formulation of SIM

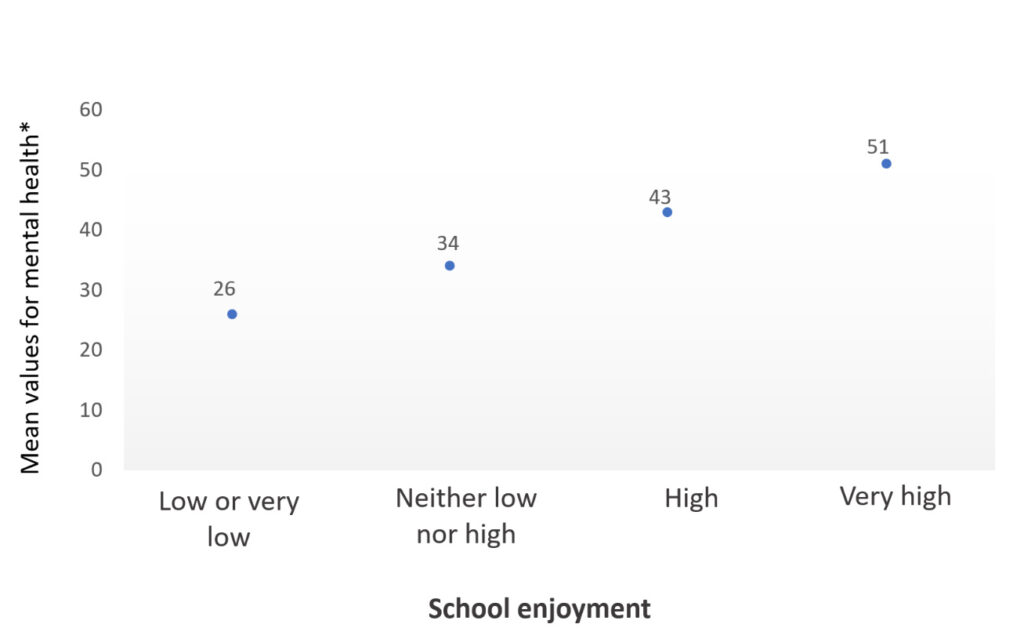

SIM – which is described in more detail in the Research tab and The SIM Method tab – is a universal intervention designed to promote mental health among students at upper secondary schools. Thus the method is not a treatment initiative, but is intended for all students, regardless of their level of mental health. The programme is manual-driven and comprises nine discussion sessions held at approximately weekly intervals. SIM is led by specially trained mentors in half classes (mentor groups) of approximately 10 to 15 students. Four topics are dealt with during the sessions, three of which have been directly taken from the MHC-SF measurement instrument – in the form of emotional well-being and also social and psychological function. The fourth topic is well-being at school and has been included because it is so strongly linked to the target group’s mental health – this is shown by both research and population surveys, such as Liv och hälsa ung. The figure below, for example, shows the link between the mean values for MHC-SF and self-reported well‑being at school – an almost linear relationship.

Students in SIM can individually choose various focus areas that they can work on as a full group, in a resource team and also individually. The purpose is to enable students to discover, investigate and develop their own resources relating to their chosen focus. The focus areas are taken directly from the indicators in MHC-SF and also from studies of what is important for well-being at school. The working method is based on a solution-focused approach and techniques, where the mentor has the role of facilitator, assigned to coach students to coach themselves and each other. Further information about the method can be found under the The SIM method tab.

References

The links below will open in a new tab.

- Stengård E, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner K. Mental Health Promotion in Young People – An Investment for the Future: World Health Organization; 2010.

Mental Health Promotion in Young People – an Investment for the Future (pdf) - European Framework for Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing. EU joint action on mental health and wellbeing.

European Framework for Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing (pdf) - SBU. Universella program i skolan för att främja psykisk hälsa bland unga 2016 [Available from:

Universella program i skolan för att främja psykisk hälsa bland unga (pdf) - Kraftsamling för psykisk hälsa. Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner.

Kraftsamling för psykisk hälsa – SKR - World Health Organization (2013). Mental health action plan 2013–2020.

Mental health action plan 2013–2020 (pdf) - Friedl L. Mental health, resilience and inequalities. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Denmark; 2009.

- Huppert FA. Psychological Well-being: Evidence Regarding its Causes and Consequences. Appl Psychol. 2009;1(2):137-64.

- Chida Y, & Steptoe A. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Mortality: A Quantitative Review of Prospective Observational Studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7), 741–756.

Positive Psychological Well-Being and Mortality: A Quantitative Review of Prospective Observational Studies - Diener E, Helliwell J, & Kahneman D. International differences in well-being. 2010. Oxford University Press.

- Huppert F & So T. Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110(3), 837–861.

Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being - Wood A & Joseph S. The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;122(3), 213–217.

The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study - Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95(3):542-75.

- Kahneman D. Objective happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schartz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. p. 3-25.

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is It – explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(6):1069-81.

- Keyes CL. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):539-48.

- Keyes C L M. (2009). Atlanta:

Brief Description of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF) (pdf)

Accessed October 31, 2020. - Söderqvist F, Larm P. Psychometric evaluation of the mental health continuum – short form in Swedish adolescents. Current Psychology. 2021;

Psychometric evaluation of the mental health continuum – short form in Swedish adolescents - Söderqvist F. Skillnader i positiv psykisk hälsa bland skolungdomar: Analys utifrån Liv och hälsa ung undersökningsåren 2014 och 2017. Folkhälsomyndigheten, Solna, 2018.

Skillnader i positiv psykisk hälsa bland skolungdomar – Folkhälsomyndigheten (pdf) - Liv och hälsa ung Västmanland 2020. Presentation av länets resultat. Region Västmanland.

Liv och hälsa ung Västmanland 2020 – Region Västmanland (pdf)