SIM, as an intervention method, is group-based coaching with young people at upper secondary schools that aims to promote mental health. It has been produced within the research project School-based intervention to promote the mental health of young people.

The SIM method has been designed to include topics that reflect the theory of mental health and how it is measured, view the Mental Health tab. It is thus based on a normative model, but – and this is important – dialogue conducted during group sessions is based on the solution-focused approach and techniques, view the

Solution-Focus tab.

In the SIM method, we start from indicators of mental health and well-being at school. We also make the assumption that all students “want to and can work on something” and that this can lead them towards the future they seek. What the student “hopes will start to happen and resources and abilities that make this possible” are investigated and reinforced during the solution-focussed dialogue. This is the motivation that we are working with in SIM.

In SIM we enable students to observe and pay attention to what is helpful in their everyday lives and accept support from the network around the student. Some of the ‘active’ components of SIM are related to behaviour change [1], such as:

- Goal attainment

- Social support

- Self-belief

- Feedback and imaginary reward

- Imagining of future outcomes.

The active components of SIM take their point of departure from the solution-focused approach and its techniques, where young people are coached, individually and as a group, in discovering, investigating and (further) developing resources with clear connections to mental health and the foundations of mental health.

The mentor functions as a facilitator for the content and process during group sessions. The mentor is referred to as a ‘group coach’, as their role largely involves coaching students and supporting students when they are coaching each other. The students can work on discovering, investigating and (further) developing resources that promote various feelings, qualities and skills with clear connections to the components of mental health and also well-being at school.

Students are coached to discover resources of importance to their mental health. This creates awareness that motivates the students to investigate their resources, something that engenders confidence in their own ability and that further strengthens their resources and the opportunity (the choice) to further develop their own ability.

Structure of the intervention at schools

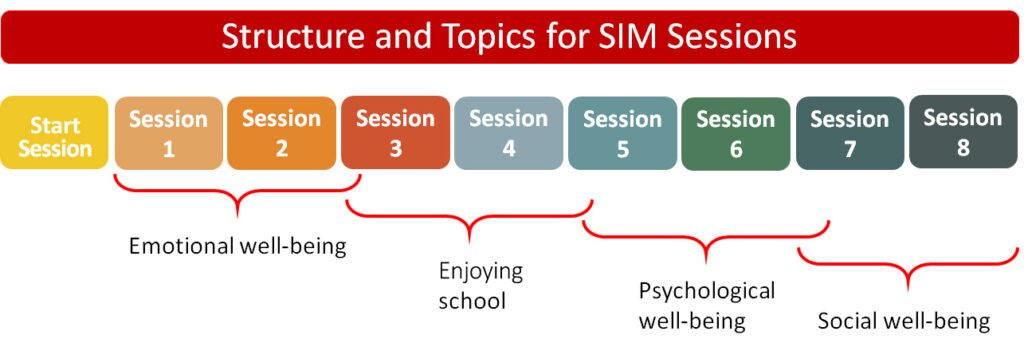

Young people at upper secondary schools participate in nine weekly group sessions. They have access to adapted material, via an app with a personal log-in, to support the coaching process. Mentors have four days of mentor training as well as instruction in the SIM method. As method support, they have the manuals, short films, PowerPoint slides and also a personal log-in for a dashboard, including the pedagogic Group Session Rating Scale (GSRS) follow-up tool, to measure and, together with the student group, reflect on their experience of group sessions and the discussion alliance [2].

Outline structure of the nine sessions

Initial session:

Introduction to SIM as a whole, mental health and solution-focused coaching. Start-up of the coaching process and resource teams.

Sessions 1, 3, 5, 7:

Introduction of topics for emotional well-being, well-being at school, psychological well-being and social well-being. Concluding follow-up of the development of the student in their previously chosen focus.

Sessions 2, 4, 6:

Follow-up of the student’s focus, coaching in the resource team and further tasks to work on to develop chosen focus.

Session 8:

Follow-up of the student’s focus, deeper reflection on the initiative as a whole, resource feed-back and focus on maintaining the impacts achieved, in the form of positive differences.

Topics and underlying focus that students can choose to work on

Students individually choose one of the indicators proposed for each topic at sessions one, three, five and seven. When students have made their choice, we refer to that indicator as ‘my focus’. The student’s own focus is chosen from the ‘emotional well-being’ topic in session one. This focus is followed up in session two and a brief follow-up is also conducted in session three. The student chooses a focus from the ‘well-being at school’ topic in session three, which is followed up in sessions four and five. Similarly, the student chooses a focus in session five, then from the ‘psychological well-being’ topic, which is followed up in sessions six and seven. The student chooses their final focus in session seven, which is then from the ‘social well-being’ topic, and this is followed up in session eight together with the initiative as a whole.

Solution-Focused Intervention for Mental Health

TOPIC:

Emotional well-being

FOCUS:

To develop my capacity to feel…

- happy

- satisfied

- involved

TOPIC:

Well-being at school

FOCUS:

To develop my capacity to…

- feel inclined to want to learn new things.

- be a good friend.

- accept support from others when I need to.

- establish a peaceful study environment.

- study in a way that helps me achieve my subject targets.

- have good conversations where I listen to others and others listen to me.

- utilise the influence I have at school.

- I choose and formulate my own focus.

TOPIC:

Psychological well-being

FOCUS:

To develop my capacity to…

- like myself.

- be myself with others.

- feel that life is meaningful.

- assume responsibility for and have strategies to deal with everyday life.

- accept challenges that help me grow as a person.

- make and retain good relationships

TOPIC:

Social well-being

FOCUS:

To develop my capacity to…

- contribute to the society in which I live.

- feel a sense of community with other people.

- identify goods things that are happening in society.

- trust other people.

- understand how society functions.

The solution-focused approach at SIM sessions

“When we create and are in the solution-building process, we are supporting each other emotionally.”

Cynthia Franklin, talk, 28 November 2018

SIM group sessions are based on the approach that deep down everyone wants something, everyone has resources and can take action and everything is constantly changing. During this process, we can identify what is most useful right now to make the future something we want it to be.

Group sessions are based on the fundamental elements and techniques of the solution-focused working method. The manual includes tangible recurrent discussion exercises and short pieces of information that build the framework of the structure of all of the sessions. In addition to this framework, the group coach uses solution-focused resource feedback and general discussion issues during the discussion process to encourage students to have strengthening discussions in line with the topic of the session in question.

A solution-focused group session cannot fully follow a manual. A solution-focused group coach for SIM listens to what the students are saying, decides on what appears helpful in terms of progressing towards what they want and builds on this by asking or confirming what the students have said.

Each student will form part of a resource team to support their desired development. Students in this resource team will be introduced to and trained in solution-focused discussions and resource feedback with a view to supporting their own development and the development of others.

“The key to engagement is to ask questions.”

Cynthia Franklin, talk, 28 November 2018

As coaches, we ask questions, but we are not just lining questions up: we are listening to the responses and incorporating them into future questions.

Useful questions may be:

- What has gone the right way…?

- What is the best, or the least bad, thing that has happened?

- How did you do then?

- What are you hoping for in the future?

- What is important for you?

- What have you done previously that worked well or to some extent?

- What did you do to make an effort?

- What was helpful?

- What made a positive difference for you?

- What is the best advice that you would give yourself, for example, to take good care of yourself today/going forward?

Students will work on the focus that they have chosen for the topic in question (for example ‘happiness’ or ‘have good relationships’) both during and between sessions. The purpose of students choosing their own focus is to create participation and reach an agreement on what the group sessions should deal with within the framework of mental health.

During solution-focused coaching, individuals may make their own decisions on the most important discussion topics. Besides focussing on when the students perceived their focus, the students are invited to work tangibly to develop and improve an ability or skill and, linked to this, do something concrete that may contribute to their chosen focus. For example, even more happiness may be perceived and on more occasions. Here the students themselves, with coaching support from the group coach and from their classmates, need to think about what skills and actions could help and what effort the student needs to make to do this successfully. This is followed up in future sessions by focussing on what has functioned well, gone in the right direction or what the student has made an effort to try to do.

References

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. (2013). The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2013;46(1): 81-95.

- Quirk K, Miller S, Duncan B, Owen J. Group Session Rating Scale: Preliminary psychometrics in substance abuse group interventions. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research.

2012;1-7.